How's Your Wyrd?

Originally published: 4/4/2017 on Weebly blog

John Muir (my 19th century Scottish clansman and naturalist and founder of the Sierra Club) said: “When we try to pick out anything by itself we find that it is bound fast by a thousand invisible cords that cannot be broken, to everything in the universe."

We are, slowly, slowly, opening (or re-opening the closed) understanding of the great mistake we made: thinking that anything is separate from any other thing – culminating in believing that we are separate from the Creator. This mistake underlies mainstream theology, economics and everything else in our culture, and wherever you look in our world and see human-enacted misery, you can see the underlying cause: believing that anything is separate from each other. This is the core difference between the indigenous world view, which sees the thousand invisible cords, and the western mind, which revels in the fantasy of individualism, culminating in many absurd notions and ways of being.

In the Nordic shamanic tradition, the word for this interweaving, interdependent connection of everything to everything is wyrd. Our word weird comes from this source – weird, meaning mysterious, uncanny, otherworldly. Wyrd refers to the interplay between what is seen and unseen, between the spirits and one’s life. Wyrd is sometimes referred to as the web, or as the weave. These images affirm what Muir said: that no act, no person, no life exists outside of its connection with other things. In the Celtic shamanic tradition, the weaving, flowing, intersecting "Celtic knot" affirms this web of interdependence.

So instead of greeting someone by asking "how are you?" we might better greet them by asking "How's your Wyrd?" or "How's your interdependence with all life, seen and seen, going?" A simple version of this, and, a highly recommended way to greet one another: "What has Spirit taught you today?"

Picture

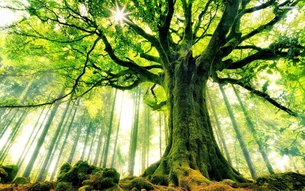

About trees, John Muir also said that you cannot define a tree by its leaves and trunk and bark and size. This of course is exactly how western taxonomy defines trees and everything else – by its separate parts. Muir said that a tree must be defined by what lives in it, off it and on it. A tree is defined by what it feeds, and what it feeds upon. A tree is literally sunshine and summer rain and iron in soil. A tree is the bugs that live under the bark and the bird that comes to peck at the bark for the bugs. A tree is the squirrel nest in the branches. A tree is the leaf-song played by the summer's wind.

We seem to spend a lot of time asking ourselves "Who am I?" But instead of that question, perhaps we should be asking, "Who do I feed, who do I eat, who lives in me and off of me; who do I shelter and sing to, and bless with my presence?" That is who I am. Try it.

I leave with you with one of my favorite poems by the 13th century saint, mystic and poet Mawlānā Jalāl-ad-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī, better known to modern Americans simply as Rumi. In it he puts an elegant voice to the drummer perspective:

Those who don't feel this Love

pulling them like a river,

those who don't drink dawn

like a cup of springwater

or take in sunset like supper,

those who don't want to change,

let them sleep.

This Love is beyond the study of theology,

that old trickery and hypocrisy.

If you want to improve your mind that way,

sleep on.

I've given up on my brain.

I've torn the cloth to shreds

and thrown it away.

If you're not completely naked,

wrap your beautiful robe of words

around you,

and sleep.

--Translated by Coleman Barks, Like This (Maypop, 1990).

John Muir (my 19th century Scottish clansman and naturalist and founder of the Sierra Club) said: “When we try to pick out anything by itself we find that it is bound fast by a thousand invisible cords that cannot be broken, to everything in the universe."

We are, slowly, slowly, opening (or re-opening the closed) understanding of the great mistake we made: thinking that anything is separate from any other thing – culminating in believing that we are separate from the Creator. This mistake underlies mainstream theology, economics and everything else in our culture, and wherever you look in our world and see human-enacted misery, you can see the underlying cause: believing that anything is separate from each other. This is the core difference between the indigenous world view, which sees the thousand invisible cords, and the western mind, which revels in the fantasy of individualism, culminating in many absurd notions and ways of being.

In the Nordic shamanic tradition, the word for this interweaving, interdependent connection of everything to everything is wyrd. Our word weird comes from this source – weird, meaning mysterious, uncanny, otherworldly. Wyrd refers to the interplay between what is seen and unseen, between the spirits and one’s life. Wyrd is sometimes referred to as the web, or as the weave. These images affirm what Muir said: that no act, no person, no life exists outside of its connection with other things. In the Celtic shamanic tradition, the weaving, flowing, intersecting "Celtic knot" affirms this web of interdependence.

So instead of greeting someone by asking "how are you?" we might better greet them by asking "How's your Wyrd?" or "How's your interdependence with all life, seen and seen, going?" A simple version of this, and, a highly recommended way to greet one another: "What has Spirit taught you today?"

Picture

About trees, John Muir also said that you cannot define a tree by its leaves and trunk and bark and size. This of course is exactly how western taxonomy defines trees and everything else – by its separate parts. Muir said that a tree must be defined by what lives in it, off it and on it. A tree is defined by what it feeds, and what it feeds upon. A tree is literally sunshine and summer rain and iron in soil. A tree is the bugs that live under the bark and the bird that comes to peck at the bark for the bugs. A tree is the squirrel nest in the branches. A tree is the leaf-song played by the summer's wind.

We seem to spend a lot of time asking ourselves "Who am I?" But instead of that question, perhaps we should be asking, "Who do I feed, who do I eat, who lives in me and off of me; who do I shelter and sing to, and bless with my presence?" That is who I am. Try it.

I leave with you with one of my favorite poems by the 13th century saint, mystic and poet Mawlānā Jalāl-ad-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī, better known to modern Americans simply as Rumi. In it he puts an elegant voice to the drummer perspective:

Those who don't feel this Love

pulling them like a river,

those who don't drink dawn

like a cup of springwater

or take in sunset like supper,

those who don't want to change,

let them sleep.

This Love is beyond the study of theology,

that old trickery and hypocrisy.

If you want to improve your mind that way,

sleep on.

I've given up on my brain.

I've torn the cloth to shreds

and thrown it away.

If you're not completely naked,

wrap your beautiful robe of words

around you,

and sleep.

--Translated by Coleman Barks, Like This (Maypop, 1990).

Comments

Post a Comment